Important Note: This is a draft version. This document is still currently in progress and will evolve in the coming months.

Today, millions of people around the world lack access to life-saving medicines because of high prices or lack of innovation. Health providers are in crisis, and have to make tough choices about what drugs they can afford to provide.

The source of the problem lies in how we reward medical innovation: by providing monopolies in the form of patents. Patents create an unavoidable conflict by using a single, per treatment, payment that must cover the cost of R&D at the same time as manufacturing costs. Under the patent system, innovators need high prices per pill to get paid and these high prices restrict the number of patients that can be treated.

Patents make this conflict between access and innovation inevitable but we could choose to to separate payment for R&D from payment for manufacture. This separation would remove the conflict and deliver strong incentives for innovators at the same time as greatly expanding access to medicines.

In this paper we explore a new model where we reward innovations using remuneration rights, and, in return, innovators provide unrestricted, royalty free access to their innovations for both manufacturing and research purposes. This would allow free-market competition in manufacturing, leading to prices close to cost of manufacturing, as well as faster, freer and more innovative research.

Is there a need for change?

The trajectory of the current system is unsustainable. Millions cannot get the treatment they need because of high prices, and innovation is inefficient; important disease areas are neglected, research is often slowed by legal disputes and licensing restrictions and a disproportionate amount of resources are used on areas of limited health impact. The patent system inevitably produces these tensions, as high prices for drugs are necessary to fund research and development.

Is there an alternative?

The remuneration rights model offers an alternative to the patent system. A remuneration rights fund would disburse payments to registered innovators based on health impact. In return, innovators would allow open access to all of their information, enabling generic competition in manufacture similar to out of patent medicines today. This would lower the prices of medicines without jeopardizing the funding of future research and development.

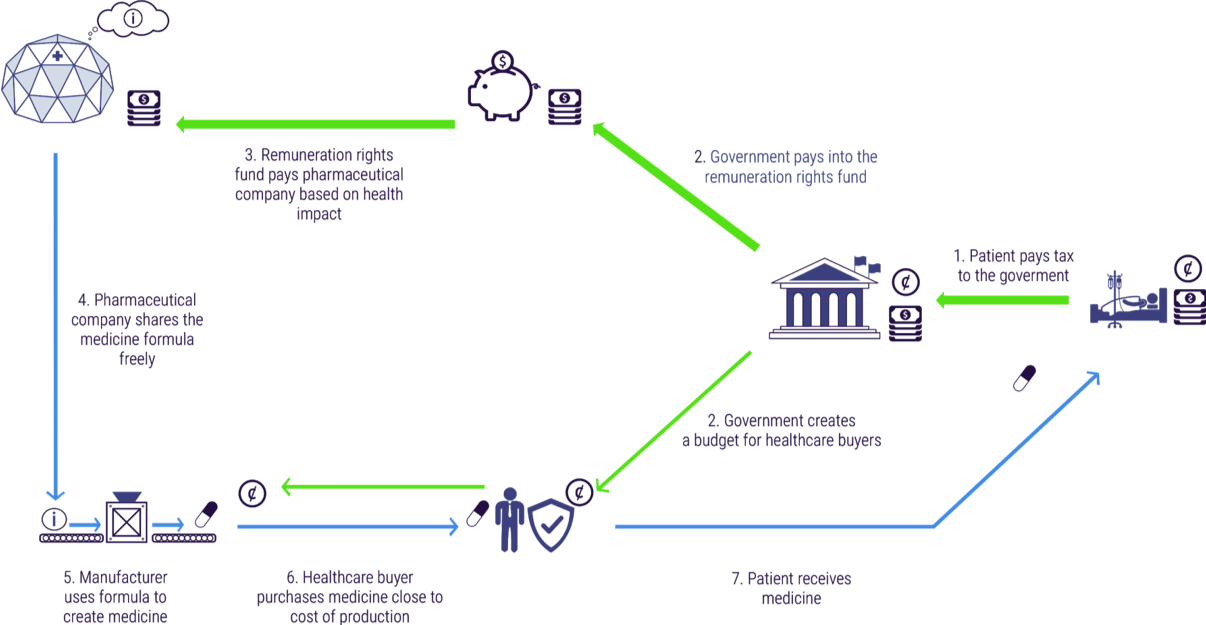

Under the remuneration rights system, taxpayers, employers and insurers would contribute towards healthcare payments just as they do today. Governments would pool these payments into an independant fund. Innovators would receive a remuneration right entitling them to a payment from the fund that reflects the health impact of their innovation. Patients would receive medicines in the same way as today, but at prices close to the cost of manufacture.

What is the impact on stakeholders?

Many groups hold a stake in how pharmaceutical research is financed. For some groups, such as politicians, shareholders, investors and basic researchers, the introduction of a remuneration rights system would make only limited changes. For others, such as patients, healthcare professionals, healthcare buyers, employers, insurance companies, taxpayers, marketers, distributors, manufacturers and innovators, the remuneration rights system would expand processes which already occur. There are also groups who would experience new roles as a result of the remuneration rights system, such as civil servants.

Are remuneration rights feasible?

Remuneration rights are technically feasible, and much of the relevant infrastructure is already in place; we already determine who own innovations and how rights can be shared between multiple innovators, and we already measure health impact. Remuneration rights are also politically feasible; sustainable funding can be ensured, governance established, and international cooperation achieved. In many instances, the relevant precedents are already in place under current systems, and national and international laws already permit remuneration rights. Moreover, transitions of this scale or larger have been successfully implemented in the past.

Such a transition can begin locally limited to a particular country or region and/or specific type of disease. Importantly it can operate in parallel with the patent system. A starting point would be a detailed feasibility study, followed by a pilot implementation of remuneration rights on a limited basis.

Are remuneration rights an improvement on patents?

The key criteria for assessing improvement would be societal welfare, equating to maximizing the number of healthy life years over the long-term. Roughly, this boils down to access, innovation and cost: it being desirable to have more access,1 more innovation and lower cost.

Remuneration rights provide increased access compared to patents. Generic competition would lower drug prices, while tying remuneration to health impact would increase the number of drugs available to poorer populations and incentivize distribution.

Remuneration rights offer the same or increased levels of innovation. Remuneration rights offer the same level and type of financial incentives as patents. Innovation might also become more effective by remunerating according to health impact rather than sale volume and allowing open access to information.

Finally the cost of the remuneration rights system for medicines would be the same or lower than our current patent-based system. The cost of the system is made of three parts: paying for innovation, paying for manufacture and paying for administration (e.g. the patent office etc). By far the largest of these is the expenditure on innovation and manufacture of medicines. Under remuneration rights these would be at a similar level to today. Administration costs would also be similar to today as remuneration rights reuse existing systems for granting and administering rights.

Pharmaceutical research and development has delivered some of the greatest achievements of the modern age, all but eradicating scourges that have terrorized humanity for generations and improving the health and quality of life of billions. But it is increasingly clear that the system by which we finance this progress is broken. Around the world millions lack access to the medicines they need to survive and thrive. Often, drugs are just too expensive, while in many areas of urgent need there are simply no medicines available to help.

The problem is global. In less affluent countries, where many pay out of pocket for medication, prices for even a short course of treatment can run to many times the average annual salary. In more developed nations, public healthcare systems struggle to afford soaring drug prices, having to ration or restrict access to the latest treatments.

These failures in access are a natural consequence of how we fund and incentivize medical innovation. Today, innovators are awarded a monopoly right on their inventions, a patent, which affords them exclusive marketing rights over the resulting product. As the research and development of new drugs is an extraordinarily expensive endeavor, the final prices innovators set on drugs are often very high in order to recoup costs, even though the actual drug itself may be relatively cheap to produce. As innovators are only paid through the final sale of the drug, prices must be high to cover these research costs. Necessarily, these high prices limit the number of people able to access the drug.

This system also skews what kinds of innovation we receive. Medicines which sell are incentivized rather than those with the most beneficial impacts on health. The closing off of vital research and information also slows down research progress. Therapies targeting chronic conditions for the wealthy have far greater potential for profit than those for acute conditions and for the global poor, and are invested in accordingly. Anti-aging products of limited health impact receive much more funding than debilitating and life-threatening conditions that impact billions.

Under the patent system - where innovators are only rewarded through the final sale of their product - access and innovation necessarily conflict; if we wish to develop any new medicines tomorrow then we must, reluctantly, restrict access today.

It is tempting, especially with increasingly strict protections on intellectual property rights worldwide, to view this scenario as an unfortunate inevitability. But there are ways to resolve the tension between access and innovation. Separating the funding of research and development from the sale prices of drugs would enable both access and innovation to flourish. We urgently need to seize this opportunity if we are to avoid the collapse of pharmaceutical innovation and healthcare as we know it.

The patent system, fitting in with a wider culture of intellectual property protection worldwide, has been so successful and dominant that it is easy to forget the instances where medical innovation has thrived without such protections. Opening up the products of research and development for wider use does not necessarily entail unsustainability and first copies going unpaid for. Even today, approximately half of all medical R&D in the United States is funded directly by the government. The histories of pharmaceutical development in India, Argentina and Italy, which did not always afford patent protection, illustrate that private sector innovation does happen without IP. It is possible to have both access and innovation, we just need to reconceptualize how pharmaceutical research and development is structured.

This paper makes a concerted effort to do that. Here, we make the case for urgently reforming the current system of medical innovation, highlighting how such a system is unsustainable and undesirable in the long term. We propose a new system, one which rewards medical innovation and access separately. This system, based on a remuneration right similar to a patent, rewards medical innovators whilst allowing free and open access to innovations so they can be produced at cost by manufacturers and other innovators can build upon their ideas.

We demonstrate that such a system is politically and technically feasible, and, most importantly, immensely desirable: it will expand access to medicines for millions in both developed and developing countries and help align innovation efforts more closely with actual health impact.

We show that many of the necessary precursors of such a system are already in place, and that the costs of implementation would be significantly outweighed by the benefits in improved access and innovation.

Ultimately, and in spite of its historical successes, the current system of medical innovation does not work. It necessarily limits access to essential medicines and, in many cases, fails to incentivize the kinds of development we want as a society. The unsustainable trajectory of this system means it is imperative to search for new mechanisms of funding medical innovation, moving beyond the ingrained trade-off between access and innovation a monopoly rights patent system engenders.

Remuneration rights do just this, and by dividing payment for drug access and drug innovation, we can refocus our medical priorities and greatly expand access at the same time. This is a huge opportunity; we can have both access and innovation at the same time and all we need to do is innovate in how how we pay for medicines. Under such a system, everybody wins.

Pharmaceutical research and development (R&D) has delivered some of the greatest achievements of the modern age: the polio vaccine, antiretroviral drugs to combat HIV, and insulin. But the system for funding R&D is broken, and heading for catastrophe. Millions of people do not have access to medicines because of the high prices charged to recoup the costs of research, and many urgent health problems go without treatments because of the lack of a profitable market. Simultaneously, profitable but insignificant areas are over-invested in. Moreover, there are structural blockers in the form of legal disputes and licensing restrictions which hinder innovation and delay us receiving the most cutting edge of medical innovation. If current trends in prices and innovation continue, these problems will worsen over coming years and become untenable. It is therefore essential that we find solutions to them now.

Rising prices combined with an aging population, demographic growth and falling therapeutic benefit make for an unsustainable system. The past decades have seen an increase in the price of medicines, and a decrease in the therapeutic benefits associated with new innovations.2 Projections suggest these trends will continue. It is therefore imperative to take action before the price of healthcare becomes completely unsustainable, and the number of new and universal medicines dwindles. Governments will not be able to afford to buy medicines for their citizens at this rate.3 Such an outcome would not only spell disaster for state budgets and ordinary citizens, but also for pharmaceutical companies’ profits. Bankrupted healthcare providers will no longer be able to purchase from pharmaceutical companies if prices rise indefinitely. Everyone has a stake in changing the system to preserve both rewards for innovation and access to medicines.

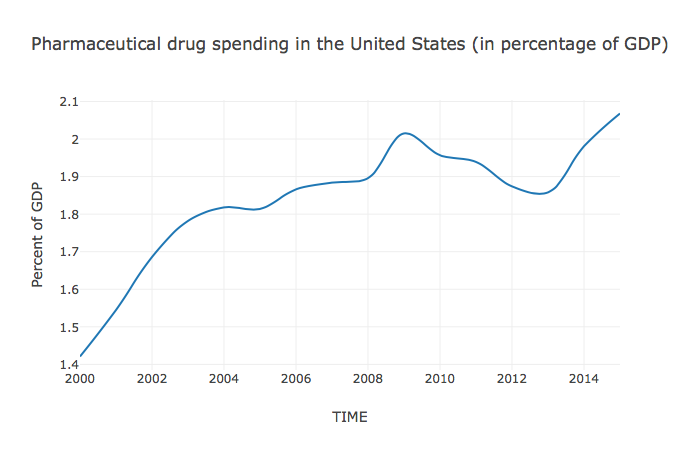

The prices of medicines are eye-watering. According to the Express Scripts Prescription Price Index, branded drug prices doubled between 2008 and 2016.4 As the Kaiser Family Foundation has demonstrated, using data from the National Health Expenditure Account, United States (US) spending on prescription drugs has been on a steep incline for decades, even when adjusted for inflation (Figure 1). In 1980, \$30 billion was spent, adjusting for inflation; in 2016 this figure soared to \$329 billion - an increase of over 1000%. Recent years have seen particularly steep increases, with expenditure in 2015 at 120% of that just two years previously in 2013.5 In 2017 alone, pharmaceutical company Pfizer raised the price of 91 of its drugs by an average of 20%.6 Such price hikes are now threatening access in even the richest of countries.

Source: “Health Spending Explorer.” Peterson-Kaiser Health System Tracker (blog). Accessed October 25, 2017. https://www.healthsystemtracker.org/interactive/.

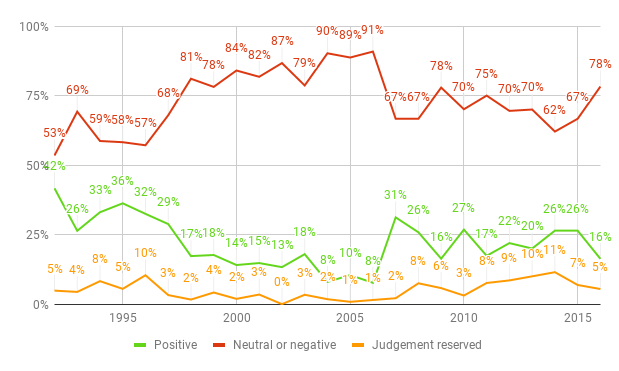

As well as getting more expensive, drugs are also getting less effective. Figure 2 shows the results of the annual review of new products and new indications for drugs already on the market undertaken by Prescrire International. Just 16% of new drugs in 2016 had even a possible advantage over their predecessors, compared with 42% in 1992. The absolute number of drugs with possible therapeutic advantage has also fallen, from 60 new drugs in 1992 to just 15 in 2016. Meanwhile, in the same time period the percentage of drugs offering no additional therapeutic benefit rose from 53% to 78%. If such trends continue, we will not only face unsustainably high drug prices in the future but also a grave shortage of effective drugs.

Sources: “A Look Back at Pharmaceuticals in 2006: Aggressive Advertising Cannot Hide the Absence of Therapeutic Advances”, p. 84; “New Products and New Indications in 2016: A System That Favours Imitation over the Pursuit of Real Progress”, p. 138.

Millions of people today do not have access to the medicines they need. The World Health Organisation (WHO) estimates that around a third of the world’s population does not have access to medicines.7 There are many reasons for a lack of access to medicines: availability, affordability, appropriate use, and drug quality.8 Affordability, a combination of price, cost and availability of funds, is a primary concern.9 This particularly affects the poor and those living in poorer countries. In wealthier countries, governments have also become unable to meet the rising costs of new medicines. Consequently, millions of people go without treatment or experience delays in doing so. This has obvious costs to the individual, but also serves to place additional strain on public healthcare systems and reduces economic productivity.

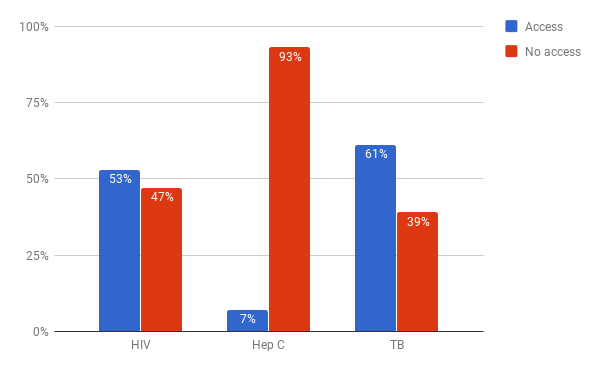

While it is difficult to find estimates on the lack of drug access globally, there are numerous cases that illustrate the low levels of access to medicines today. The WHO estimate that in 2008, 8.8m children died from vaccine-preventable illnesses.10 In 2017, the WHO claimed that 1.5 million deaths could be prevented annually if vaccination coverage improved.11 Figure 3 shows access figures for three high-burden diseases: Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), hepatitis C and tuberculosis (TB). The numbers of people who currently go untreated for these diseases is staggering: 16 million with HIV,12 66 million with Hepatitis C, 13 and 4.1 million with TB.14 It is unclear exactly how many of these people would be able to receive treatment at close to marginal cost, but even with very conservative assumptions, it is clear that many millions are unable to access medicines because of unaffordably high drug prices. This is especially important given the threat to global health security posed by conditions like HIV and multiple drug-resistant TB. Everyone benefits from increased access to medical treatment, not just the poor or the sick.

Sources: “GHO | By Category | Antiretroviral Therapy Coverage - Data and Estimates by Country.” WHO. Accessed October 25, 2017. http://apps.who.int/gho/data/node.main.626; “GHO | By Category | Treatment Coverage - Data by WHO Region.” WHO. Accessed October 31, 2017. http://apps.who.int/gho/data/view.main.57056ALL?lang=en];“Global Hepatitis Report, 2017.” World Health Organisation, 2017. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/255016/1/9789241565455-eng.pdf?ua=1; “WHO | Hepatitis C.” WHO. Accessed October 25, 2017. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs164/en/.

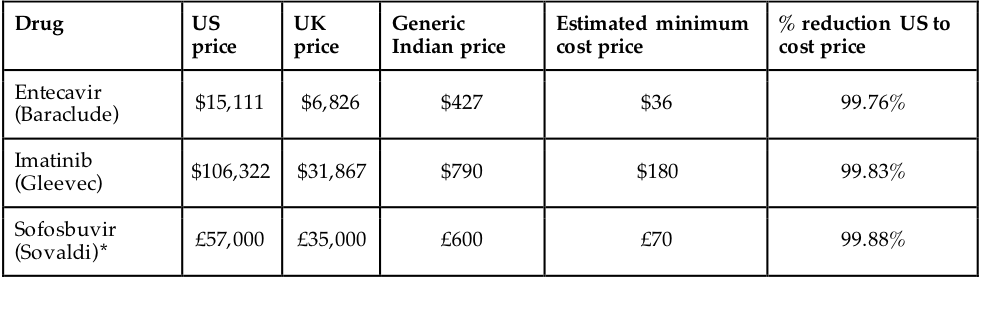

These systemic and persistent failures inaccess are directly caused by the patent system. Patented medicines are produced exclusively and without market competition, consequently being sold at prices far above the costs of manufacture. Figure 7 in Section 6.2 gives examples of the huge gap that is often present between the cost of manufacture and the sale price of a medicine. This gap exists to compensate for high R&D costs. Under the patent system, such high prices are not just likely: they are necessary. The way that the patent system funds innovation, which we need if we are to continue to have new medicines developed, is through high prices today, restricting access for those who are sick in the here and now.

In spite of the incentives for innovation generated by patents, there are a number of serious problems with the way in which innovation operates today. A critical role of the pharmaceutical industry is to create new medicines which benefit society, but equally vital is to make these products available to those who need them. The current patent system is not achieving this requirement. Because financial incentives for innovation are tied to the market, unprofitable but important areas of health are neglected; simultaneously, profitable but relatively insignificant areas in terms of health impact are heavily invested in. Finally, there are structural blockers to research , such as patent disputes and licensing which unnecessarily delay and complicate the development of new medicines.

Ultimately, the reason that pharmaceutical innovation matters is for people to be healthy. Pharmaceutical companies are motivated by this philosophy, but they also have a responsibility to their shareholders. Yet profitability is a poor proxy for health, especially given wealth inequalities. Many of the most widespread and serious diseases primarily affect the poor (e.g. malaria). As the people who suffer from these diseases cannot afford to pay large amounts for medicines, the market does not provide a sufficient incentive for pharmaceutical companies to conduct the necessary R&D. A similar effect can be observed with chronic and acute diseases: as those with chronic illnesses continue to need medication, it is more profitable to invest in research for chronic needs than acute but serious illnesses. This means that important areas of health are systematically neglected in the R&D pipeline.

Neglected diseases include malaria, TB, diarrheal diseases, and tropical diseases; they are defined as diseases that affect people in low-income countries and are a leading cause of mortality, chronic disability and poverty. Over a billion people live with one or more neglected tropical disease.15 In 2010, “Only about 1% of all health R&D investments were allocated to neglected diseases.”16 And “in 2013, public and private investment for R&D in 34 neglected diseases was \$3.2 billion, of which pharmaceutical corporations only contributed \$401 million. The latter amount represents only 0.8% of total industrial R&D spending of \$51.2 billion in 2014”.17 The global landscape of health R&D shows a substantial gap: diseases of relevance to high-income countries were investigated in clinical trials seven-to-eight-times more often than were diseases whose burden lies mainly in low-income and middle-income countries.18 Monopoly patents do not offer a sufficient incentive to innovate in these areas, because the people affected by these diseases are mostly poor. In a system where profit is tied to sales, drugs to treat these patients will not be developed. This has a huge human cost for those who suffer from such diseases, and also poses risks to the world at large. Unchecked tropical diseases increase the risk of global pandemics like ebola, while entrenching poverty and so increasing global instability. It is better for human society if leading causes of mortality and morbidity are treated.

On the other hand, profitability does incentivize areas of research which have low health impact, or in some instances no health impact at all. The profit incentive is insensitive to how large a therapeutic benefit a treatment will have. Provided that a sufficiently large or sufficiently wealthy market exists, there are incentives for R&D. This leads to areas of low therapeutic significance being over-researched - a poor allocation of resources from the point of view of social welfare.

It has been estimated that much of the neglected tropical disease burden, which impacts 1.4 billion people in South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa, could be alleviated for just \$300 million to \$400 million a year.19 However, the current mechanisms for rewarding medical innovation simply do not provide avenues for the return on investment for this kind of research.20 It simply does not happen, or does so in a much diminished capacity, often requiring state or philanthropic support. In fact, much more money is spent each year on the cosmetic anti-ageing market: the global anti-aging market was valued at \$140.3 billion in 2015,21 in spite of the limited health impact it generates.

Provided a drug can be sold legally and to a sufficient extent, it is profitable to make, even if it does not represent any real improvement on existing drugs.22 In 2005, Love and Hubbard claimed that “probably one-half to two-thirds of the R&D investments were directed towards projects of almost no medical significance”.23 And “an analysis of 1345 new medicine approvals in Europe revealed that no real breakthroughs occurred between 2000 and 2014; only 9% of new medicines offered an advance, and 20% were possibly helpful”.24

Alongside these problems of allocation, there are also structural blockers to research of all kinds under the patent system. Patents are a monopoly rights and are explicitly designed to limit anyone other than the innovator from using the information or accessing the knowledge behind an innovation. Those who do not follow these rules are harshly penalized. As a result, costly management and infringement settlements are pervasive.25

Legal disputes can stall innovation for many years, preventing new medicines from reaching the public. Historical examples include the telephone, the radio and the automobile.26 Moreover, failure to obtain a license from a patent holder means that potential innovators cannot proceed. A good example of this is the monopoly over breast cancer genes formerly held by Myriad Genetics. Until the patent was revoked, further research and more widely available and affordable testing were stalled.27 In contrast, the opening up of intellectual property has proven to be effective boosters for innovation. In the aftermath of the First World War, compulsory licensing of German chemical patents in the US significantly improved innovation there.28 This indicates that patent enforcement can slow down R&D.

There are good reasons we use patents: they provide effective incentives for innovation, ensuring that innovators are rewarded. Simply voiding patents, as some people have argued, is unlikely to be a viable solution either practically or politically. If patents were simply to disappear private investors would be left with little incentive to undertake expensive R&D at all, and future generations would see a deficit of new medicines.

Unfortunately, the patent system also creates a fundamental tension between access and innovation. More access means less innovation and vice-versa. With patents, high prices are needed to fund innovation but high prices mean fewer people can be treated (crucially, the lost purchases of those who cannot afford treatment benefit no-one as the patients remain sick and the pharmaceutical company gains no revenue). Conversely, lowering prices for medicines to increase the number of patients with access would mean less money for pharmaceutical companies to invest in innovation.

As a society we obviously want both access and innovation. At an extreme, one is practically worthless without the other: imagine a world in which everyone has access to what medicines there are, but there are virtually none available; conversely, imagine a world in which all diseases have a cure but no one can afford them. The patent system trades these two things off against one another. Without systemic change, there is no way around this fundamental dilemma: either one increases access and decreases innovation, or one increases innovation and decreases access.

Given the ubiquity of the patent system, and a broader culture of protecting intellectual property29 this trade-off can seem natural or inherent. However, the trade off is merely an artefact created by the nature of patents as a funding mechanism. Medicine is made up of two parts: information and manufacture. The information part of medicine is intangible, produced through R&D, and extremely expensive. The manufactured part of medicine is physical, produced in factories and relatively cheap to make. Patents create a single payment for these two elements of medicine: both R&D and the manufactured pill are paid for by the consumer, be they a government, an insurer or an individual patient. Because patents combine the payments for these two elements, the cost per usage of a given treatment must be high to cover the R&D. This means that the number of treatments that can be afforded by a given healthcare consumer is limited, and many are denied access as shown in Section 2.2. And this denial of access is necessary under the patent system: otherwise R&D will not be incentivized in future.

But it is possible to pay for R&D and manufacture separately, thus resolving the conflict. By splitting the single payment of the patent mechanism into two, the price of each individual unit of a medicine can be drastically lowered, while maintaining high incentives for innovation.

We need a new approach at this critical juncture. A point where millions are unable to afford access to essential medicines and where even in the richest countries soaring prices are leading to rationing and a crisis in funding. We need a two-part payment system that pays separately for innovation and manufacturing medicines delivering both high levels of investment in innovation and high levels of access to affordable medicines. Remuneration rights do just this

We propose an alternative kind of property rights,30 remuneration rights, as the best alternative to the patent system for medical innovation. Under remuneration rights, innovators would obtain a non-monopolistic “remuneration right” rather than the monopoly patent they receive today. Remuneration rights entitle their owner to payment from a central fund according to the value generated by the innovation: how much a given drug improved health. In return, the innovation would be open for use and manufacture by everyone, improving access and further facilitating innovation.

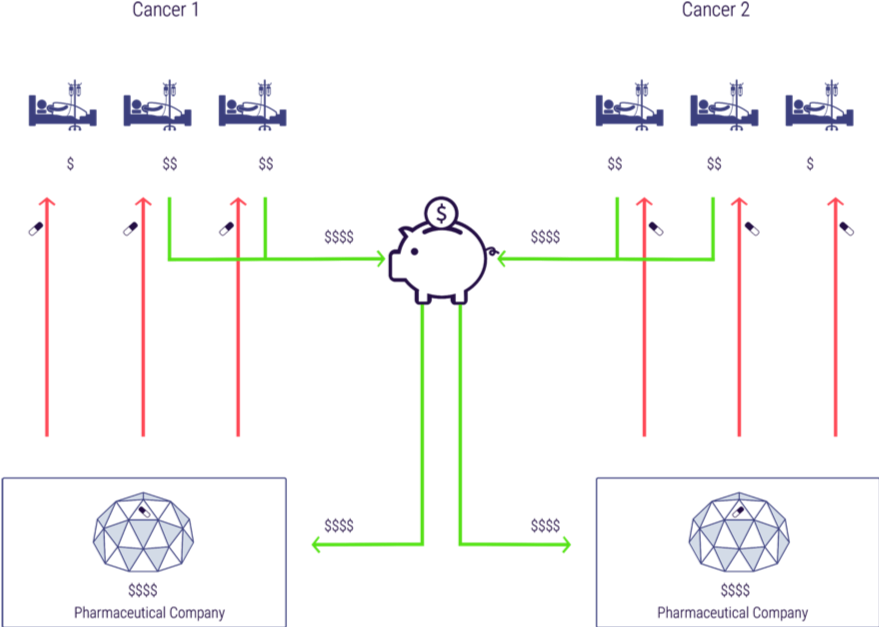

Figure 4 depicts the core aspects of the remuneration rights model. Pharmaceutical companies and other innovators undertake R&D and create new medicines. Innovators register for a remuneration right instead of a patent. In exchange for a remuneration right, all R&D has to be freely available to any certified manufacturers to produce. This enables competition among manufacturers to make high quality, cheap medicines. Healthcare buyers purchase these medicines at prices close to the cost of manufacture. Lower prices per pill dramatically increases patient access to medicines. Meanwhile, citizens continue to pay taxes to their governments. Governments pass a small proportion of their health care budget to health care buyers to purchase medicines. A much larger proportion is paid into an independent remuneration rights fund. This fund disburses its funds on an annual basis to the owners of registered innovations. Each innovation is rewarded in proportion to the health impact it produced.

Crucially, under the remuneration rights system, medicines and R&D are paid for separately. Currently when we pay for a medicine we are paying both for the expensive R&D (perhaps billions in total) and for the cheap cost of manufacturing (perhaps just a few dollars per pill). As an example, when we pay \$50,000 for a medicine perhaps 99% (\$49,500) is going to pay for the R&D and 1% (\$500) is paying for the manufacturing.

With remuneration rights, the billions of R&D cost are paid for via the remuneration rights fund, and the hundreds of dollars to manufacture the medicines are paid through current channels of drug purchasing. Because the price of medicines is close to the cost of manufacture, people can get the treatment they need. Meanwhile, innovation is still paid for and incentivized through the remuneration rights fund.

Figure 5 shows how medicines and monies would flow under the remuneration rights system, using the example of a simplified world with two cancer drugs. Patients in this example (all insurees/taxpayers normally) would contribute to the remuneration rights fund, which would disburse money to innovators to pay for R&D (the two richer patients in the diagram with \$\$). Competition in manufacturing would mean the medicines would then be available to all patients and monies from the fund would be distributed to the relevant innovators proportionately to use and impact (in this case we assume the benefit of each treatment is the same and so the monies are distributed to the manufacturers 50:50). In this case the ultimate distribution of monies to innovators is exactly the same under remuneration rights as under patents but in contrast to the patents case all three patients receive treatment. (Note, for simplicity we have omitted manufacturers from this diagram as we are seeking to illustrate the distribution of monies to innovators).

We already have substantial sources of funding for medicines in the form of healthcare budgets, divided amongst direct grant giving and indirect funding through drug purchases. This funding comes from taxpayers, employers and insurers. Under a remuneration rights system, these groups would continue to contribute healthcare payments as today. In government-based health systems, this money would come primarily directly from taxpayers and employers. In insurance-based health systems, much of this money would be paid first in insurance contributions, and then transferred on by insurance companies.

Governments would pool existing contributions into an independent remuneration rights fund. There are a number of ways the level of funding might be determined. One way would be to set a percentage of GDP for each participating government to contribute. Another would be to set the size of the fund at the current level of private spending on pharmaceutical R&D, and grow the fund at the current level of growth in private research spending. The fund would have a fixed disbursable pool available for innovation funding each year. Governments would be legally bound to fulfil their respective contributions. Once governments had deposited their funds, they would no longer have control over the allocation of the monies, ensuring the independence of the fund.

Innovators would apply for a remuneration right from a remuneration right office, similar to patent offices today. This right would not grant market exclusivity, and would enjoin open access to the information behind the innovation. Instead this right would entitle innovators to be paid from remuneration rights fund based on the impact of their innovation on health.

Specifically, each year, the disbursable funds in the remuneration rights fund would be divided up among the holders of remuneration rights, in proportion to the health impact they created. Where innovators build upon the ideas of others, a portion of their remuneration right would be set aside like a royalty, to be delivered up to the originators of the relevant innovations. Health impact would be estimated using a predetermined and transparent metric. There are several examples of these metrics today, like the Quality-Adjusted Life Year (QALY) or Disability-Adjusted Life Year (DALY), which are used by institutions like the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and the WHO.

In this way, remuneration rights have a strong market-like aspect: payment is determined by individual usage and its benefits. In some respects they are similar to patents, but without the disadvantage of creating monopolies. And just as patents have a limited term, remuneration rights would eventually expire. This would ensure that money continued to flow towards newly invented treatments, and would reduce the need to keep track of the impact of older treatments, which might be infrequently used or simply superseded.

Access would increase dramatically at no cost to innovation and with little or no increase in spending. Citizens would pay their tax (or insurance contributions in insurance based systems) just like today. There might be small additional cost of additional manufacturing as lower prices mean we choose to expand access. The overall result is vastly increased access to medicines for patients.

The way in which patients receive medication would remain the same - but the price to themselves, their insurers or their health system would fall per treatment. Given that millions of people currently do not have access to essential medicines, this could mean a huge increase in health outcomes for a small additional investment.31

=

There are many important groups involved in the funding, research, development, manufacture, distribution and use of medicines. Remuneration rights would change the experience of some groups operate, while leaving that of others little changed. This section sets out in detail the implications of the remuneration rights system for some of the most important stakeholders in the medical ecosystem.

Patients receive medicines in the same way as today, but more treatments are available to them at much cheaper prices.

Patients would continue to use prescription medicines paid for by the parties currently responsible, be they government, insurance companies or patients themselves. What would change for patients under remuneration rights is that more treatments would be available. Currently, expensive treatments are rationed or not provided at all in many countries. Separating the cost of the medicines themselves from the cost of the R&D would mean that each additional treatment, rather than costing hundreds of thousands of dollars, might cost hundreds or even less.

Healthcare professionals continue to prescribe as today, but with access to greater treatment volumes.

Doctors, pharmacists and other healthcare professionals would continue to prescribe medicines as they do today. However, they would have access to many drugs which are currently too expensive to prescribe at all, or in all but the most serious cases.

Healthcare buyers can purchase medicines from a greater range of manufacturers at greatly reduced prices.

Healthcare buyers would be able to choose between a wide range of manufacturers when purchasing medicines. This would give them greater power to negotiate prices, which in any case would be driven far lower than today thanks to competition in manufacture.

Civil servants implement the fund according to predetermined, predictable and objective guidelines.

Civil servants would implement the transition to the remuneration rights model, and would then operate the fund itself. This would be a significant task for countries participating in the remuneration rights fund. The nature of remunerating innovations based on health impact is more technical than discretionary, which enables transparency and predetermination of selection criteria.

Politicians can deliver much greater health care and remain independent of decisions about health impact.

Politicians would be able to deliver greater health care for only a comparatively trivial increase in funding (to cover the low cost of manufacture for additional physical medicines). Meanwhile, they would remain independent of decisions about health impact, allowing these decisions to be made without undue political influence and sparing politicians hard decisions between treatment types.

Employers pay health care contributions as today, and their employees can access much greater levels of treatment for similar cost.

Employers would continue to pay insurance contributions for their employees, either at the same or a very slightly increased rate (to cover the low cost of manufacture for additional physical medicines). Their employees would receive far greater levels of access to medicines in exchange for this similar input. This can be expected to increase productivity , minimize sick days, and boost employee wellbeing.

Insurance companies pay into the fund, and their insurees can access much greater levels of treatment for similar cost.

Insurance companies would pay contributions into the fund. Their insurees would receive far greater levels of access to medicines. Meanwhile, insurers would benefit from the vastly reduced price of medicines. Overall, insurers would pay slightly more (to cover the cost of manufacture for additional pills) for greatly increased health coverage.

Taxpayers would continue to contribute to national health budgets. The slightly increased expenses of the system (in paying for the manufacture for many more pills) would mean slightly more money spent on healthcare (though this could potentially be offset by efficiency gains). In exchange, taxpayers would benefit from drastically increased access to medicines.

Shareholders continue to receive profits from pharmaceutical companies.

Pharmaceutical companies would remain profitable businesses, but their profits would be tied to health impact rather than to pure sales. Shareholders would still receive these profits. Furthermore, the structure of the remuneration rights fund would deliver greater certainty to investors about the long-term revenues available to the industry.

Marketers continue to market drugs. Marketing undertaken by manufacturers feeds into profits for the owners of the remuneration right.

There would still be a need to market drugs. Although profits would no longer be tied directly to sales, as health impact is related to the number of patients treated, there would be an incentive to market effectively. Competing manufacturers would use marketing to increase their market share. Ultimately, innovators would benefit from marketing undertaken by manufacturers: it would increase the use and therefore the health impact of their innovation, and so lead to a greater payment from the remuneration rights fund.

Distributors have an expanded remit, as rewarding innovation based on health impact provides a financial incentive to distribute to hard-to-reach patients.

Distributors of pharmaceuticals would experience vastly increased incentives to reach more marginal patients. Currently there is only an incentive to distribute to wealthy markets, as remuneration is based on sale price alone. Under the remuneration rights system, as remuneration is tied instead to health impact, there is a stronger incentive to distribute to poor markets too.32 This would encourage distributors to expand into emerging markets, as well as increasing global access to medicines.

Qualified manufacturers can produce any medicine in competition with other manufacturers.

Manufacturers would have license and royalty free access to any innovation registered with the remuneration rights office. This would expand the opportunities for manufacturers whilst ensuring high quality production at competitive prices. Manufacturers would still be subject to extensive quality control, so drug quality would be maintained.

Innovators file for remuneration rights instead of patents and are paid annually from the fund.

As producers of information, innovators would file for a remuneration right. They would then be entitled to a share of the remuneration rights funding pool for a fixed period of time. Payments would be made annually. The payments to the rights holder would be proportional to the usage and health benefits of the treatment.

As consumers of information, innovators would have unrestricted access to research and information on all innovations registered with the remuneration rights office. This would reduce duplication and accelerate cumulative research.

Investors get returns from R&D that delivers health impact.

Investors continue to receive returns on investments in pharmaceutical R&D. The only difference is that the most successful investments would be in the innovations which produce the most health benefit, rather than in the innovations which sell best.

Basic researchers continue to be funded through research grants.

Basic researchers would still be funded through research grants, as today. Grants are a push funding mechanism, and fund research upfront, rather than after the fact.33 This is the most suitable way to fund early stage research, as it permits exploratory work into new research areas, without predetermining specific outcomes.34

In order to represent a viable alternative to the patent system, remuneration rights must be technically and politically feasible to implement. Technically, many of the aspects required under a remuneration rights system already exist; we already have robust means of measuring health impact, the patent system requires ways of defining innovation ownership as well as what happens when patented innovations are built upon by others. Each of these mechanisms could be reused for remuneration rights.

Furthermore, much of the political infrastructure required for a remuneration rights system is already in place, including coherent international (and often national) legislation and means of arbitration that could be co-opted, similar governing bodies for related funds, and the means of securing sustainable funding. This means there are few significant barriers to a transition to a remuneration rights system.

For remuneration rights to be a viable funding mechanism, the technical aspects of the model must be practicable. Three issues stand out:

Delimitability. Remuneration rights require the determination of which innovation belongs to which innovator.

Reuse. As research is cumulative, it is important that the remuneration rights model can reward innovators who build on the work of others in a proportionate manner, while not disadvantaging the originator.

Health impact measurement. Health impact must be measurable in a reasonably accurate way for remuneration rights to be allocated appropriately.

Fortunately, there are precedents for all three of these technical features.

It is crucial to both the patent and the remuneration rights system that innovations can be separated from one another. In order to give a right, whether a patent monopoly right or a remuneration right, to an individual, we have to be able to attribute innovation correctly. This process is vital in the patent system, could be substantially reappropriated under a remuneration rights system.

Because it aims to confer special privilege over a particular innovation, the question of delimitation is central to the patent system and therefore well defined within that framework. When submitting a patent application, the goal for the innovator is to demonstrate that the product (or treatment) represents a significant innovation originating from the applicant. The application process is itself a delimitation exercise which defines the innovation.

Remuneration rights cover the same sorts of innovation patents do, and would be delimitable in the same way. To qualify for a remuneration right, innovators would have to prove that they were the originators of a particular medicine or treatment in the same way they currently do when applying for patents. The infrastructure of the current system can to a large extent be maintained: the patent office would simply become the remuneration rights office. Aside from the end product, very little would change.

Remuneration rights would be granted on the condition of completely open access to all information relating to the innovation. This would enable innovators to build on previous ideas more easily. It is therefore important that remuneration can be shared fairly between originators and innovators who build upon these.

This already happens in the patent system, albeit to a more limited degree. Because research is cumulative, reuse is frequent and important in medicine, although it is inhibited by the blockers discussed in Section 2.3.3. Under the patent system, follow-on innovators are required to pay royalties to the original innovator.

Within the remuneration rights model, anyone would be free to build on the work of others. In a similar fashion to royalties in the patent system, follow-on innovators would be liable to pay a proportion of their own remuneration rights payments to those whose work they built upon. These proportions might be standardized for simple cases or, for more complex cases, the two parties could negotiate, with ultimate recourse to the courts if no mutually acceptable solution were found. In other words, if an innovation built upon a previous innovation holding a remuneration right, then a proportion of the right granted to the secondary innovation would be set aside for the initial innovator(s).

The major difference with the patent system would be that the original innovator would not have an absolute right to prohibit reuse as they do today. Rather, they would have the right only to \“equitable remuneration\”. This change would favor the follow-on innovator, while ensuring that the originator was fairly compensated. The remuneration rights model would therefore make it easier for innovators to build on and incorporate previous work, preventing the delays seen today.35 The system would operate along the same lines as the patent system today, but without the right to prohibit reuse.

Remuneration rights depend on the measurability of health impact. While any measurements would be inexact, there are several good measurement systems which could be deployed, some of which are already in use today.36 Some jurisdictions already use these to determine their medicine purchases: for example, NICE in the United Kingdom (UK) uses QALYs to decide whether or not a medicine is cost-effective.37 The remuneration rights fund would extend the methods and data gathering procedures that already exist, creating a rich pool of information for improving healthcare in general while simultaneously rewarding innovation more fairly.

There are several sources of data that would be used to assess the health impact of a particular innovation. Initially, clinical trial data would be used as a baseline for the efficacy and therapeutic benefit of a drug. Today clinical trials showing safety and efficacy are already required for all new pharmaceuticals so this data is already being collected. As time passed, observational data would become available on the actual benefits caused by the medicine. Additionally, we also already track prescribing data so that the number of treatments given out can be calculated.38

No health impact assessment will be perfect. Data will be incomplete, and some things will be difficult or controversial to quantify. But health impact assessment need only be accurate enough that the best strategy for companies seeking remuneration rights is to actually produce health benefits.39 Moreover, because companies are competing for a fixed amount in the Remuneration Rights Fund for Medicines they have an incentive to hold each other account and check fraud and abuse (if company X fraudulently overstates the use and health impact of their treatment this reduces the monies for competing company Y).

As well as functioning technically, remuneration rights must be able to operate politically. This includes the sustainable financing of the fund, the fund’s governance structure, the relationship between the fund and governments, and the legal status of the fund.

For the fund to function reliably on a global scale, two essential conditions must be met: international agreements binding all countries to contribute to the fund, and a systematic way to set equitable contribution levels must be agreed upon.

Before pooling contributions into an independent remuneration rights fund, it is essential to prevent potential free riders from benefiting from the efforts produced under the remuneration right model, both within and between countries, without contributing to the fund themselves. A remuneration rights fund without such safeguards against freeriding would be unsustainable. This could be done by establishing international agreements under which countries bind themselves to minimum levels of medical research funding, as happens with military spending. Governments would be legally bound to fulfil their respective contributions, which would ensure the fund would have a fixed disbursable pool each year. Once contributions were deposited, governments would no longer have control over the allocation of the monies.

The size the fund of could be determined in two different ways. First, it could be benchmarked on the the current level of private spending on pharmaceutical R&D, and grow at the current level of growth in private research spending. In the US, for instance, current levels of public and private research funding together amount to \$100bn a year (depending on exactly how medical research is demarcated). Alternatively, each country could agree to allocate a given percentage of their GDP, perhaps 0.5% to 1% of GDP, raised primarily out of general tax revenue. As an illustration, 1% of GDP for the United States would amount to about \$186bn a year.40 In time, the fund would need to be adjusted to follow inflation and demand for healthcare. The level could also be adjusted to reflect the level of development between countries, with richer countries committing themselves to higher proportions.

The fund would be governed by an independent body. Stakeholder participation would be important to ensure that participating states are willing to join the remuneration rights fund.41 Transparency would also be vital, to create trust in the operating of the fund. Ultimately, the most important feature of the governing body would be its impartiality. One way of achieving this would be to make governance independent of electoral politics and political faction. Another might be to separating the performance of health impact assessment from the establishment of guidelines for the same.42 This would minimize the discretionary function of health impact assessment and reduce the risk of external influence being exerted.

Specific governance designs have already been proposed by previous proposals operating along similar lines to a remuneration rights fund:43

The Medical Innovation Prize Fund Act (MIPF), submitted most recently to Congress in 2017 by Bernie Sanders, proposes a national remuneration rights-style fund for medical research in the US.44 The system would be administered by a board of trustees and six expert advisory boards. There would also be a system of competitive intermediaries, who would compete for funding and allocate some of the rewards.45

The Health Impact Fund (HIF), proposed by Aidan Hollis and Thomas Pogge in 2008, would be a voluntary, global remuneration rights fund:

“The HIF will be governed by a Board of Directors chosen by funding partners, exercising primary responsibility over the Fund. The Board will oversee three branches representing the core functions of the Fund: the Technical Branch, the Assessment Branch, and the Audit Branch. These will, respectively, set the standards for evaluation of health impact (Technical), determine individual products’ actual impact (Assessment), and ensure correspondence between standards and evaluations (Audit).“46

Such designs would need to be considered in a feasibility study. Our proposal builds upon these previous models.48

The remuneration rights fund would operate in a global context, liaising with many governments. There are questions about both cooperation between participants of the fund and between the fund and non-members. The most crucial point of tension in implementing and maintaining a remuneration rights system will be how to negotiate the potential issue of free riders, whereby non-members enjoy the benefits of open-access without contributing towards R&D costs.

There are questions remaining as to whether the fund could operate successfully on a national level or whether wider international cooperation would be required. There have been proposals for national remuneration rights-style funds like MIPF,49 and a pilot study might well be national in scale. Other advocates think that a minimum viable level of participation pertains. For instance, the proponents of HIF regard the minimum threshold to be a fund comprising states representing a third of global income.50 Whether the fund is national or international in scope, participants would need to contribute sufficiently to encourage innovation. To obtain the full benefits of the fund, member states would also need to have a lively manufacturing sector; generic competition tends not to lead to marginal cost unless there are 10 or more competitors.51

At least initially, there would likely be states operating outside of the remuneration fund. This raises the question of non-members exploiting the open-access nature of the fund without contributing towards it, and of members requisitioning patented innovations elsewhere, to manufacture internally, without compensating patent holders. Core to governing this relationship would have to be a mutual recognition of patents and remuneration rights. Members of the remuneration rights fund would continue to respect the IP rights of non-member states and alternative means of payment may need to be developed for non-members wishing to use innovations in the fund.

International treaties, differential pricing agreements or some other means of translating between the two systems will need to be established to allow a successful coexistence of both systems.

There is extensive national and international legislation covering the patent system. The remuneration rights model is compatible with these legal frameworks. The most important of these is the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS), which is compatible with the remuneration rights system.

The patent system, while still defined and enforced in national jurisdictions, has been internationalized through the TRIPS agreement. TRIPS governs nearly all aspects of intellectual property in international trade. Prior to TRIPS, different countries had different patent laws, which often reflected their level of development and the social goals that patent laws were thought necessary to achieve. Today, TRIPS requires all World Trade Organisation member states to maintain strict patent protection laws for patented pharmaceuticals, with a guarantee of at least 20 years of market exclusivity.

While the patent system enforced by TRIPS is global and binding, it also has built-in flexibilities. Legal provisions are in place to allow exceptions to exclusive rights in order to widen access and bypass the patent monopoly under specific circumstances. Referred to as “compulsory licensing”, these flexibilities allow the use of patented innovations without the consent of the owner in cases of (public) non-commercial use, national emergencies, other circumstances of extreme urgency, as well as in anticompetitive conduct. Article 30 of TRIPS clarifies that exceptions to exclusive rights must be limited, must “not unreasonably conflict with a normal exploitation of the patent,\” and must “not unreasonably prejudice the legitimate interests of the patent owner, taking account of the legitimate interests of third parties”. Provided that a remuneration rights fund where set at a sufficiently high level, it would therefore qualify as a legitimate exception, as it would take the interests of innovators into account through sufficient remuneration.52 These flexibilities are already in place, legal and would allow remuneration rights to function without requiring additional legal frameworks to be created.

Other examples of TRIPS compliant (and legal), but non-patent-based, funding mechanisms exist. Prize funds are a good example. For instance, the Longitude Antibiotics Diagnostics Prize offers \$10m for a diagnostic test which helps to conserve antibiotic use.53 Patent pools are also used today to increase access to medicines. The Medicine Patent Pool (funded by UNITAID) aims to reduces the cost of drugs treating HIV, viral hepatitis C and TB by pooling the licenses required for future development, making it it easier for innovators to create new drugs. They negotiate directly with pharmaceutical companies to encourage them to voluntarily join an HIV patent pool.54 Thus, generic manufacturers can obtain licenses more easily, increasing competition and reducing prices.55

Overall, remuneration rights would be legally compatible with existing international law governing intellectual property. There are also mechanisms on a national level that would allow for disputes to be resolved. Remuneration rights could use existing intellectual property legislation for dispute resolution. In case of a disagreement on remuneration allocation, parties could apply for arbitration to the courts, similar to the patent system today.

Sections 4.1 and 4.2 have shown that a remuneration rights system would be feasible. There is also a question of whether it would be feasible to transition from the present patent system to a remuneration rights model. Firstly, many aspects of the current funding system would remain unchanged under remuneration rights, making the transition less traumatic. Secondly, there is the option of having remuneration rights coexist with patents, permanently or for a transition period. Finally, transitions of this scale have happened in the past without deleterious effects.

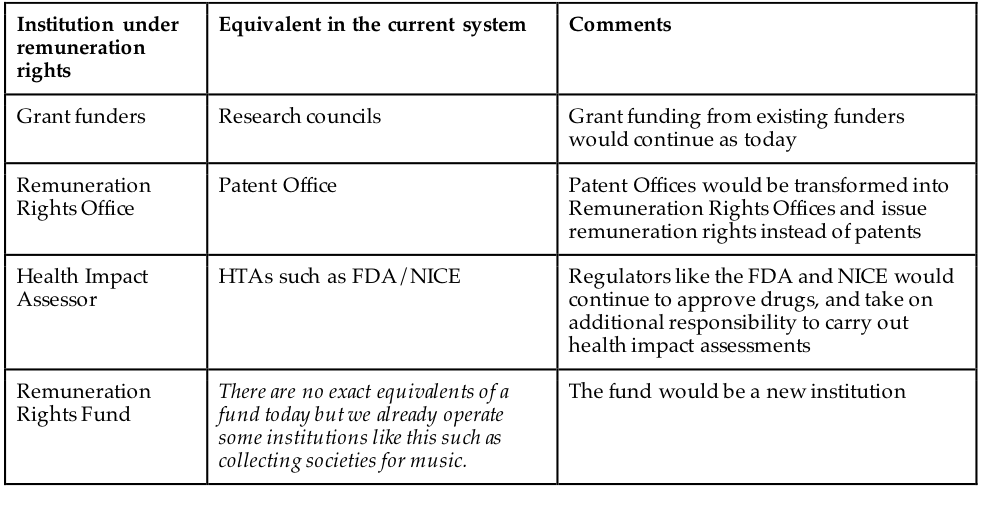

Many aspects of the current funding landscape for pharmaceuticals would remain unchanged under a remuneration rights model. Figure 6 sets out the main institutions of the remuneration rights model, with their equivalents under the current system. First, academic-style funding for research would continue largely unchanged. Remuneration rights would be examined and issued much like patents and could be done by existing patent offices. A new agency (or department, for instance, of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA)) would be established to carry out the healthcare impact assessment that would be the basis for awarding funds. A funding body would be established to manage the remuneration rights funds. It should be legally and managerially independent of government but with clear operating parameters.

Institution under remuneration rights Equivalent in the current system

Grant funding from existing funders would continue as today Remuneration Rights Office Patent Office Patent Offices would be transformed into Remuneration Rights Offices and issue remuneration rights instead of patents Health Impact Assessor HTAs such as FDA/NICE Regulators like the FDA and NICE would continue to approve drugs, and take on additional responsibility to carry out health impact assessments Remuneration Rights Fund There are no exact equivalents of a fund today but we already operate some institutions like this such as collecting societies for music. The fund would be a new institution

The changes required to transition to a remuneration rights system could also be rendered less dramatic through a coexistence with patents. Firstly, there is a choice between replacement of prospective patents only, and retrospective replacement. Either way, new medical discoveries would be given remuneration rights, rather than patents, and the question is whether existing patents would be permitted to continue until expiry, or whether these would be converted into remunerations rights with immediate effect. Conversion would have the advantage of simplicity, but the remuneration rights might need to be supplemented by compensation for the sake of fairness.56 If on the other hand only future innovations were to be granted remuneration rights, then patents and remuneration rights would operate alongside one another for a transition period. This could be particularly appropriate as a starting point. Feasibility could be assessed by implementing remuneration rights on a limited basis, which would focus on either a specific area (per country or region) or disease area and operate in parallel of the patent system.

It could also be decided to retain patents permanently in parallel to remuneration rights.57 This would give innovators the choice of filing for either a remuneration right or a patent. In this scenario, the remuneration rights fund would be most attractive for innovations with high demonstrable health impact among low-income populations, where patents offer a weak incentive, and patents would be most attractive for innovations serving wealthier groups with lower health impact. However, this mixed approach would substantially lower the potential benefits and add to complexity so we generally recommend a systemic switch to remuneration rights.

Remuneration rights could also be made more attractive, relative to patents, in a variety of regulatory ways. A large remuneration rights fund would mean the rewards under remuneration rights are high. Government spending on patented drugs could be sharply limited. There could also be direct taxes on income from patents. Full analysis of the implications of these choices over the status of patents under the remuneration rights system must be undertaken in a feasibility study. But the option certainly exists to minimize the transition further by retaining patents temporarily or permanently.

These considerations show that the transition to remuneration rights need not be as dramatic as they first appear. But it is also true that changes of comparable magnitude have been made before without deleterious consequences. The foundation of the National Health Service (NHS) in Britain and of the European Union (EU) and its predecessor alliances are stand-out examples of structural reforms, that occured on a larger scale, that were successful. The establishment of these institutions required profound structural realignment, of a much wider nature than the remuneration rights fund, and on a multinational scale in the case of the EU. They offer reassuring precedents for the implementation of new institutions. There is evidence that the formation of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA)58 and the entry of the UK into the European Economic Community (EEC)59 did not cause economic disruption, in spite of the scale of these regulatory changes. The remuneration rights model is more limited in its scope than the NHS, NAFTA or the EEC. However, there are parallels of a more comparable scale within the field of pharmaceutical funding mechanisms. The institutionalisation of government research funding in the form of research councils is one such example.60 Such examples demonstrate that it is possible to implement large systematic changes without causing major disruption. Indeed, research by LPL Financial LLC indicates that in the wake of significant events since 1950, the Dow Jones has tended to rise between 3% and 5% after only one month, following initial negative reactions.61 These examples, and typical stock market behaviour in response to major events, suggest that remuneration rights could be introduced seamlessly.

Some general conditions are likely to tend towards successful transitions of this scale. Firstly, it is important that any such transition is consistent with existing international law. Remuneration rights would qualify as a TRIPS flexibility and so meet this condition. Secondly, there must be a sufficient need to justify and motivate a transition on this scale. The problems of access and innovation highlighted in Section 2 amply meet this demand. Thirdly, careful planning is required to avoid shocks to the markets. This would involve extensive work with relevant stakeholders, and capacity building. Such an approach in the case of remuneration rights would particularly involve working with governments, non-governmental organisations and pharmaceutical companies; and building manufacturing capacity. A final criteria likely to tend towards successful large-scale transitions is testing. As already mentioned, remuneration rights could be phased in using pilots or other forms of transition. This would allow lessons to be learned and design to be strengthened, without causing disruption.

A remuneration rights model is superior to patent-driven systems in terms of access, innovation and cost. Remuneration rights offer significant advantages over patents in terms of increasing access and increasing innovation (and its impact), and importantly it does not pit them against each other. Though there would of course be some costs associated with a transition to a remuneration rights model, these would be negligible compared to the benefits of the new system.

The most important criteria for comparing funding mechanisms for pharmaceutical R&D are access, innovation, and cost. These can be defined as follows:

Access. The proportion of potential beneficiaries of a given treatment who actually receive the treatment.

Innovation. The extent to which a given funding mechanism incentivizes innovation based on health impact.

Cost. The operational cost of the system.

Access to medicines increase substantially under a remuneration rights model. In the patent system, the only source of income is through the sale of the final drug, meaning the price of this must reflect both the costs of manufacture, which are low, and R&D costs, which are high. Consequently, only those with sufficient resources can access the drugs produced, and there is a strong incentive to develop marketable, but not necessarily impactful, drugs. There are also few incentives for pharmaceutical companies to distribute their drugs widely beyond the affluent markets that can afford them.

Under remuneration rights, there will be two payment streams, meaning R&D costs are remunerated separately from the sale of drugs. Open information and lack of market exclusivity would encourage competition in manufacture, which would lower drug prices without threatening innovation. Moreover, as remuneration rights are allocated in proportion to health impact rather than market profitability, a new incentive is created to research medicines for conditions mainly affecting the poor. This would increase the number of medicines available, as well as lowering the cost of each individual unit. Companies creating medicines in a remuneration rights based system would also have an incentive to distribute their medicines as widely as possible (provided that the medicine has a positive health impact for the recipients).

The WHO estimates that around a third of the world’s population does not have access to medicines.62 Even assuming only a minority of these people are prevented from accessing medicines because of affordability, decreasing the cost of medicines would still be a health intervention of huge import. Evidence suggests that the generic manufacture remuneration rights enable would lead to significantly reduced prices; when there are 10 or more competitors producing a drug, generic prices approach marginal cost.63 Such costs are likely to be much lower than the prices of branded drugs the patent system requires. Figure 7 illustrates this. The history of antiretroviral drugs, used to combat HIV, also highlight this: under intense international pressure, between 2000 and 2013, prices dropped from \$10,000 per person per year to \$100, a reduction of 99%.64 Given such differences, remuneration rights would significantly improve access when compared with the patent system.

Source: Hill, Andrew. “Generics – the Facts.” presented at the 21st Annual Conference of the British HIV Association (BHIVA), 2015. [http://www.bhiva.org/documents/Conferences/2015Brighton/Presentations/150422/AndrewHill.pdf]{.underline}.

There are important conditions that need to be satisfied in order to lower prices through generic competition. First, only a country or group of countries with multiple pharmaceutical manufacturing firms would be able to generate sufficient competition to lower prices. For a remuneration rights model to be effective, this capacity will need to be already in place, developed prior to launch or be supplemented otherwise.

Second, in some countries most of the supply chain for medicines is owned by pharmaceutical companies. This could potentially restrict generic competition under a remuneration rights system, if wholesalers owned by particular pharmaceutical companies refused to buy from competitors. If participant countries had more open supply chains, this would not be an issue. For cases like the UK and the US, where supply chains are owned by pharmaceutical companies to a large extent, national competitive tendering could resolve this problem.66 Denmark uses such a system today, and drug prices have fallen substantially since 1995, even in the absence of the remuneration rights system.67 Sweden, Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium also operate similar tendering systems for particular sets of drugs.68 While tendering systems require careful design, they tend to lead to reductions in price.69

The most common argument against reducing drug prices is that it will harm future innovation. This argument makes sense in the patent system, where access and innovation are directly traded off against one another. However, the remuneration rights model allows more access while maintaining the same or greater levels of innovation, and does not structure these principles in conflict. The remuneration right itself offers a financial incentive, just like a patent, to undertake research. Provided that the size of the fund were adequate, innovators would receive just as much as under the patent system. Moreover, remuneration rights could also stimulate more effective innovation. Medicines of greater health impact would receive greater remuneration, and those of lesser less. This would direct innovation more effectively, so that for the same amount of money more social value is created and a greater number of people helped. It is also likely that the amount of innovation would increase in a remuneration rights system, as open information permits faster improvements upon the innovations of others.

Patents provide a financial incentive to innovation through market exclusivity, enabling high prices to be charged and costs for R&D recouped through sales. Remuneration rights provide a financial incentive too, in the form of payments from the remuneration rights fund. Provided that this fund is adequately resourced, then incentives for innovation could be maintained at current levels.

Remuneration rights could also incentivize more effective medical innovation. Under the patent system, profits are tied to units sold, not the innovation’s impact. Consequently, when those in need of medicines do not provide a profitable market, for example through poverty or low usage rates, patents fail to incentivize innovation. Given the associations between wealth and health, this is a problematic way of stimulating innovation. First, the poorer you are the more likely you are to be in ill health. Second, diseases are distributed differently between rich and poor populations, meaning that the poor often have different medical needs to the rich. Finally, where cost-effectiveness is concerned, the opportunities for health impact are often especially high in resource poor settings, where general levels of health are poorer and cheaper basic interventions can have a large impact. This compounds the problem. As Scotchmer puts it, “a research agenda driven by patents is hostage to the market and to consumer sovereignty. The consumers who are sovereign are those with resources.”70 Patents stimulate the innovation that wealthy consumers are willing to pay for, and not the innovation that sick consumers need. As Section 2.3 showed, patents are currently failing to incentivize innovation in important disease areas, and over-stimulating less important research. In contrast, remuneration rights incentivize innovation in direct relation to health impact. Profits would be larger for medicines with greater effect, which would be a combination of the severity of the illness treated and the number of patients treated. This means that more effective innovation would be incentivized by remuneration rights than by patents.

Finally, there is also a chance that greater openness in research and innovation would actually increase levels of innovation under the remuneration rights system when compared with patents. Countries such as Italy, Argentina and India for many years did not have patents on drugs, yet they still had very vibrant, innovative and dynamic pharmaceutical industries with substantial innovation in both processes and products. However, with the introduction of patents their industries saw substantial concentration, often coupled with a decline of local industry and the associated innovation.71 Research in other fields suggests similar processes. For instance, the US chemicals industry saw a rapid increase in innovation after the First World War, when German chemical patents were given compulsory licenses, opening information and research to US companies.72 The remuneration rights system could provide a similar boost to innovation while ensuring the innovator is compensated for his work.

Benefits in terms of access and innovation have to be weighed up against the costs of running and transitioning to a remuneration rights system. Transition costs would be considerable. Operational costs would be the same or slightly higher than those associated with the patent system. Comparing these costs with the benefits associated with the remuneration rights system suggests that it would be a better funding mechanism than patents.

Transitioning from the patent system to a remuneration rights model would create large additional costs, albeit for a temporary period. New institutions would have to be established and old ones repurposed; possibly both systems would have to be administered alongside one another for a time. There would be costs to business as new processes were implemented for registering for remuneration rights and for monitoring health impact. A feasibility study should cost such a transition fully - but the total figure would clearly be in billions of dollars.

The transition accomplished, there are then the operational costs of the remuneration rights model to consider. The two most detailed previous proposals to advocate for remuneration rights, MIPF and HIF, provide ballpark figures for the cost of such a fund. MIPF, which would cover all medical innovation in the US, proposed funding levels of 0.55% of GDP annually.73 This would amount to something like \$80 billion.74 HIF, which would be a partial fund operating globally alongside patents, suggested an initial funding level of \$6 billion annually.75 Assuming that HIF represented one third of global product, this would mean a contribution of around 0.03% of GNI annually.76 The suggested costs of HIF and MIPF range widely in part because the funds are designed on different scales, and in part because no rigorous costing analysis has yet been undertaken for remuneration rights models. This would be essential in a feasibility study. At the present time it is clear that billions and probably tens of billions would be required to operate a remuneration rights fund.

Though the remuneration rights model would likely cost billions of dollars to implement, much of this would be offset. The sponsors of the 2011 MIPF bill estimated that the scheme would reduce the cost of drugs in the US by more than \$250 billion.77 This would more than cover the proposed \$80 billion cost to implement the fund. The designers of HIF note a similar phenomenon:

“The net incremental cost to the partner countries would, however, be a fraction of this [0.03% of GNI], since there would be substantial savings from paying low prices on new, patented medicines registered with the HIF… These small net costs are associated with much larger benefits. They would stimulate the development of widely accessible new medicines that greatly reduce morbidity and premature mortality worldwide, would thereby improve global economic performance, and would also reduce dangers from heretofore neglected diseases.“78